Mixing Up the City -El Mejunje

estamos aquí,/we are here

con la sensación/with the feeling

de no ver la luz/of not seeing the light,

pero no verla es mejor/but not seeing is best

luces nunca tuvo nuestra casa/lights, our house never had[1]

Between the late 1980s and early 1990s two global events shook the daily lives of Cubans, the socialist bloc’s collapse and the advent of AIDS. The acute economic depression euphemistically labelled Special Period, caused by the former, would eventually trigger the country’s third wave of mass migration to the US known as the ‘rafter’s crisis’. City life grew dimmer as the Soviet oil ran out and a cordon sanitaire was efficiently established by means of the compulsory interment of HIV positive people in sanatoria.[1] Amid this gloom, in the city of Santa Clara,[2] at the centre of the island, provincial boredom was being exorcised in a midnight ritual as a group of bohemians drank a mejunje, a sweetened concoction made of a random mixture of herbs, served by host, actor and writer Ramón Silverio, who would become one of the most effective alternative place-makers and urban re-animators in post-Revolutionary Cuba when his tertulia, after sometime of vagabondage around the city centre, was finally allowed to settle in vegetation and rubble colonized roofless ruins, 200 meters from the city’s main plaza.[3]

In this essay I argue that the cultural platform and place El Mejunje (named after the said mixture) has made a crucial contribution to the liveability of the city of Santa Clara. Liveability has been defined as “the degree to which a place supports quality of life” (Zanella, Camanho, & Dias, 2014, p.698), and as comprising amongst other attributes, harmony, accessibility, and high amenity (Ibid). El Mejunje has facilitated these conditions through social inclusion, bridge-building and promotion of marginalized or emerging forms of artistic expression. By so doing it has positively impacted on the collective image that residents and Cubans have of Santa Clara and has advanced the city’s global connections.

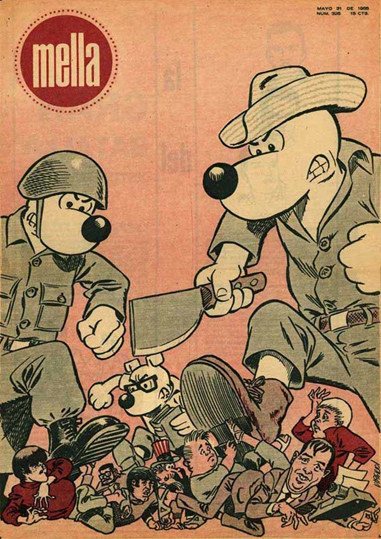

Opacity, Fragmentariness, Liminality and Play

In praising urban improvisations as drivers of “vitality and intensity of public life,” Brazilian architect Paola Jacques defines opaque zones, in opposition to spectacularized spaces, as “spaces of closeness and creativity, contrary to the luminous zones and spaces of exactitude” (2011, p.1). Spectacularization of urban spaces by designing an orderly scenography that excludes the opaque citizens and their demotic performances is mostly associated with capitalist modernity and neoliberal urban design (cfr. Boano & Talocci, 2014; Chakravarty & Negi, 2016) and the post-1959 Socialist Cuban government was certainly never interested in this agenda. If anything the prevailing assessment is that after a short spell of remarkable new architecture it neglected the city for the sake of more urgent investment in prefabricated social housing in the outskirts and in rural areas (Freeman, 2012). However, the government was averse to the “demotic vitality” (Jacques, 2011, p.1) of opaque people, rather than spaces, and particularly hostile to dissension: In the mid-sixties wars were waged on miniskirts and boys with long hair, the intellectual look of beards and sandals, effeminates and rock and roll (Castellanos, 2009; Fornet, 2008). By the mid-1960s men suspected of homosexuality could be sent to the UMAP[1] work camps, and as early as 1961 the short free cinema piece PM, a peek into the night time bar scene in the working-class neighbourhoods near the port of Havana, was banned for supposedly misrepresenting (mostly black) working class as “apparently apolitical (…), alienated from their economic and racial status, only interested in dancing, music and drinking, a world away from the Revolution’s ‘new man’[2] (Reid, 2017, p.31).

In the wake of the PM incident, Fidel Castro set the blueprint for the country’s cultural policy during the historic Words to the Intellectuals: “inside the Revolution, everything goes; outside the Revolution, no rights”[3] while the ‘Padilla affair’ in 1971[4] inaugurated the darkest period of censorship known as the Grey Quinquennia (1971-1976), which other see as much darker than grey and longer than five years.[5] It left numerous casualties, including national treasure Virgilio Piñera, playwright, essayist and poet, repressed and ostracized both as insufficiently revolutionary and as homosexual (Goicochea, 2012). During the institutionalization period of the 1970s a bureaucracy for the management of artistic culture was homogenously applied on every province and municipality, ruled from Havana and locally administered by a Soviet-style commissariat. It is in this sense that I perceive a parallelism between how Cuban urban spaces were performed and lived in terms of their social and cultural ambiance and the uniformity and standardization of pacified scenographic cities “apparently destitute of inherent conflicts, of discord and misunderstanding…” (Jacques, 2011, p.1).

El Mejunje was opaque, fragmentary and liminal in form, spirit and ethos from birth. This new creature could not be readily labelled as a cultural centre, a bar, a café, or an artistic venue. It was intermittently homeless; flatly rejected by some officials, tolerated by others and supported by few.[6] This fluidity of format and content, lack of explicit social mission, its embracing of urban discards (ruinous buildings) not just as acceptable but as desirable headquarters, and of social (human) discards, bordered on heresy in the period of its genesis 1984-1991 inasmuch as dominant discourses and structures find it difficult to assimilate fragments; that is, “minority cultures, dissident tracts, oppositional gestures.” (McFarlane, 2017, p.15).

El Mejunje started as a spontaneous gathering of the kind of people that to that point the State had meticulously controlled through affiliation to registered associations -poets, writers, actors, visual artists, musicians. It was a place of ‘play’, understood as “the common creation of selected ludic ambiances”, deprived of [financial, professional, performative] competition (Jacques, 2011, p.1). A troupe of opaque ‘groupies’ gradually joined in attracted to the ‘play’ but also to the non-intimidating physical and sociocultural dimness and fragmentariness, which in turn they reinforced: homosexuals, school drop-outs and rockers (frikis), alcoholics, HIV positive people, bored neighbours, a few rascals[7] and a random trickle of “slow men” or “ordinary practitioners of the city” (Jacques, 2011, p.2). They were not programmatically rescued in a ‘community project’, just allowed in by the way the place and the platform were organically performed. Over time the arty intellectual tertulia became a pioneering venue for marginalized genres such as rap, hip hop, rock and drag shows and a national flagship of inclusion, especially of the Cuban LGTB community.

Access, Inclusion and Bridging

The monetary schemes around El Mejunje’s subsistence have always been informal and non-important. It relied on a base of loyal volunteers, usually members of the LGTB community as very few staff were in the State’s payroll. The entrance fee ranges between 2 to 5 CUP (0.25 euro) but the physical and social membrane between the inside and the outside of the site remains soft and so does fee collection. Loyal regulars (mejunjeros), as much part of the place’s identity as the performing artists, pay at will. Drinks are sold in its tavern Tacones Lejanos[8] but one can very happily bring rum, soda and snacks from the neighbouring shops to share with friends during performances and DJ sessions. The new cafeteria extension at the front, more of a day-time place and open to street life, sells your ordinary, second class coffee[9] and artificially coloured, instant soft drinks -as they would say in Cuba, El Mejunje is still very much a ‘Cuban pesos kind of place’, a perception that goes beyond financial considerations to include an element of humble normality in the feel of the materiality of the place. The cafeteria is used in the mornings as a station of sorts, colonized by an eclectic gang of performing artists who wait for the buses that take them to work in the all-included hotels in the keys north of the province -the place refuses to wear the robe of intellectual / artistic elitism and snobbery and retains its utilitarian and down-to-earth spirit of service.

For many years city residents thought of El Mejunje as a gay bar and meeting place of marginal people; therefore, the last place ‘decent’ families would wish their young offspring to go. Yet, gradually first, then by storm, the city’s youth, which includes the thousands that study in the second largest university after Havana’s, (15,394 enrolment in 2016/17), many of whom come from the central and eastern provinces and rural areas, appropriated the site as their recreational heaven. Although freedom of sexual orientation and gender identity has always been at the forefront of El Mejunje’s collective image, what always stroke me was the harmonic convergence of different age groups and of groups (self) defined by different aesthetical preferences.

The invasion of the young, at least during the period I can give testimony of (late 1990s-early 2000s), did not displace the old. Good Luck Fridays, a favourite slot of university students, was for years headlined by Los Fakires, a local band of traditional Cuban music that would not normally feature in youngsters’ mp3 devices. The lead singer, a short, skinny gentleman in his seventies wearing a signature hat and going by the nick name Cascarita (´Small fruit peel’) was the absolute star of the night, rivalled only by the impromptu solos of their saxo player, who was well into his sixties.[10] After Los Fakires closing act the DJ would play Argentinian pop-rock idol Fito Páez and the rock-and-timba hits of the Spain-based Cuban project Habana Abierta. The older adults would either join in or look on from the side-lines, but not retreat.

El Mejunje also hosts curious aesthetical encounters; for example, slots devoted to Mexican folk songs, particularly popular amongst the semi-rural and rural population, and to ‘juke-box’ boleros from decades past, attract an audience that consumes them for what they are, no second readings, but also a more sophisticated one that flirts with kitsch and nostalgia. The unplanned convergence of these groups ends up creating areas of sincere aesthetic commonality and sociability.

Images -El Mejunje and Politics

Images 1

In many online videos of the well-known drag shows at El Mejunje, framed photographs of Che Guevara and Fidel Castro can be seen on the wall of the main stage. This captures in my view the constant negotiation of bits of freedom that takes place between art and the State in Cuba but equally the complex and shifting political consensus including how imaginations of ‘la Revolución or ‘el Che’ are decoupled from the ‘government’. Most importantly, El Mejunje, as alternative and bottom up as it wishes to be, can only exist with the approval and support of the government.

This platform was offered its definite location by local authorities and thus allowed to blossom during a transition period. The 1990s economic, social and institutional crisis created room for more autochthonous and irreverent artistic discourses and less centralized channels of production and distribution as the Soviet-style orthodoxy weakened. This decade was marked by the iconoclast postmodernism of ‘los novísimos’ (Uxó, 2006), a wave of young writers born after 1959; an explosion of conceptual art bred in Havana’s art schools (Redruello, 2010) which gained international acclaim, and the belated homages to intellectuals and artists blacklisted in the 1970s. By 2001 most of Virgilio Piñera’s plays were being staged;[11] John Lennon got a statute and The Beatles an annual celebration concert. By the 2007 the UMAP work camps and the Grey Quinquennia were being openly discussed in intellectual and professional culture circles -never too far from Havana or outside these circles.

Since the 1990s the regime has been getting better at pragmatically adjusting the ‘inside-outside the Revolution’ line traced in 1961, increasingly unconcerned with freedom of form and turning a blind eye to political critique as long as not too bold and expressed through innuendo. Artists have been getting better at encoding bolder political critique in metaphor and humour or just withdraw to an apolitical realm of spirituality, religion, personal relationships, communion with the wider world and nature, especially if unwilling or unable to leave the country. Most of the lyrics penned by members of the nationally acclaimed Trovuntivitis, Santa Clara’s own trova movement born and bred at El Mejunje since 1997, are in my opinion representative of the second tendency.

Images 2

Circa 2012, I attended a performance by the Havana-based theatre company El Ciervo Encantado, as part of El Mejunje’s theatre festival. The hilarious monologue addressed the boom of international bread-and-breakfast tourism on the island. The character, a self-employed, illegal travel agent with dubious credentials, opens the play by hanging up a glossy poster of Fidel and Raúl Castro holding hands high in a gesture of unity and strength; a type of poster that is ubiquitous (and mandatory) in State-managed institutions. The polysemic humor of this move made the audience roar with laughter. These acts of ‘mischief’ coexist at El Mejunje with acts of ‘propriety’ such as the one described at the beginning of this section (Images 1). In that respect, El Mejunje remains a place of political liminality, constantly negotiating its right to exist with the State and its legitimacy as a place of contestation and catharsis with artists and audiences.

Conclusion -Santa Clara

El Mejunje has reinforced the construction of Santa Clara as art-loving, bohemian and open-minded. The place-making agency of El Mejunje has thus spilled out of the site and its immediate surroundings and onto the city and beyond. Myers (2010, p.19) notes how art festivals (“the festivalization of African cities”) “are crucial sites of worlding, often for smaller cities.” El Mejunje is indeed a source of glocalization for Santa Clara: the place’s reputation of inclusion has reached the LGBT community outside Cuba; it is a nationally coveted venue that attracts high-quality music and theatre to the city; members of its own music movement, La Trovuntivitis, have had successful solo careers and created loyal audiences in Buenos Aires and Barcelona, without having to relocate to Havana, which reinforces the city’s liveability for artists.

Thirty years on the place has been beautified and expanded, it has created strong commitments with State institutions and garnered recognition and awards. It has been tamed and therefore lost much of the liminality and opacity that made it so special for over a decade, but by declining to adopt elitist and exclusionary tactics (financial, spatial or aesthetical), still without a manifesto, just by doing, it remains quite unique in the context of Cuba’s cultural scene, especially for its ability to effortlessly make room for all without becoming generic.

[1] Unidades Militares de Ayuda a la Producción (Military Units to Aid Production), active between 1964/65 and 1968/69. Men suspected of homosexuality and various ideological deviations were sent to these units to perform mostly agricultural labour. For more contextual information on the rejection of rock and roll, certain ‘foreign’ looks and effeminates see images in the annex.

[2] My translation from Spanish. The original PM banning statement can be found in Castellanos, 2009, p.2, footnote 2.

[3] My translation from Spanish. Original text by Departamento de Versiones Taquigráficas del Gobierno Revolucionario (Department of Shorthand Transcripts of the Revolutionary Government) 1961 (Cuba.cu, unknown) .

[4] Heberto Padilla, diplomat and poet, author of the award-winning yet censored book Fuera de juego (Out of the game), was arrested for political reasons, released in 1971 and compelled to pronounce an awkward meaculpa speech in front of an audience of writers and artists. (Fornet, 2008 and Castellanos, 2009).

[5] The Introduction to the book Política cultural del periodo revolucionario… (Cultural Policy of the Revolutionary Period…) is entitled “How many years and of which colour?” And its essay on architecture “The Bitter Tri-Quinquennia” (Navarro y León eds., 2008).

[6] Official support materialized in 1991 when the ruins were allocated to Silverio by the Municipal Assembly of the People’s Power, although in interviews Silverio has singled out the open-mindedness of one particular official with enough clout to get this approved.

[7] What the dogmatic discourse of the time would have labelled as ‘lumpenproletariat’.

[8] Tacones Lenanos is the original title of High Heels (1991), one of Spanish film maker Pedro Almodóvar’s best known works. His ouvre is iconic for the Cuban LGTB community not only for its anti-homophobic content but also for its drag aesthetics, homage to kitsch and melodrama. Almodóvar’s films brought about a revival of Cuban boleros, especially as performed by the “great tragic singers” of the 1950s and 1960s such as La Lupe and Marta Estrada. El Mejunje is very much infused with this aesthetics both in literal and performatic/symbolic ways.

[9] Lower quality coffee mixed with chicory or peas, such as the one sold under the ration card in State-subsidized food shops and in the cheaper tiers of the black market, as opposed to the ‘real coffee’ sold in hard currency shops (‘café de verdad’ or ‘café café’).

[10] This band of septuagenarians with a distinct format and sound, was ‘discovered’ in 2001 thanks to their El Mejunje revival and taken on tour in Spain where they recorded an album, which can be likened to a smaller scale reedition of the Buena Vista Social Club phenomenon.

[11] Piñera died in obscurity in 1979.

[1] “Cuba has the lowest HIV prevalence at 0.05% in the Americas and one of the lowest in the world.” (Perez, 2004, p.1). The very controversial compulsory internment became optional as of 1994 and since 2003 all HIV patients live in their homes (de Arazoza et al., 2007, p.2). The social trauma left behind by this strategy has inspired the recent Cuban film El Acompañante (The Companion; 2015, Pável Giraud).

[2] Municipality and capital city of the Province of Villa Clara. Population 245, 470 (ONEI, 2016).

[3] For a historic account on the origins and evolution of El Mejunje as reported by its founder see Fonseca, 2016.

Bibliography

Boano, C., & Talocci, G. (2014). Fences and Profanations: Questioning the Sacredness of Urban Design. Journal of Urban Design, 19(5), 700-721. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2014.943701

Castellanos, E. J. (2009). El diversionismo ideológico del rock, la moda y los enfermitos. Ciclo de conferencias del Centro Cultural Criterios: Política cultural del periodo revolucionario. Memoria y reflexión (p. 34). La Habana. Viewed on https://www.scribd.com/document/299083105/Ernesto-Juan-Castellanos-El-diversionismo-ideolo-gico-y-el-rock

Cuba.cu (unknown). Discurso pronunciado por el comandante Fidel Castro Ruz, Primer Ministro del Gobierno Revolucionario y Secretario del PURSC, como conclusion de las reuniones con los intelectuales cubanos, efectuadas en la Biblioteca Nacional el 16, 23 y 30 de junio de 1961. Retrieved from http://www.cuba.cu/gobierno/discursos/1961/esp/f300661e.html

Chakravarty, S. (2016). Exploring Urban Change in South Asia : Space, Planning and Everyday Contestations in Delhi. New Delhi: Springer India. Retrieved from http://limo.libis.be

de Arazoza, H., Joanes, J., Lounes, R., Legeai, C., Clémençon, S., Pérez, J., & Auvert, B. (2007). The HIV/AIDS epidemic in Cuba: description and tentative explanation of its low HIV prevalence. BMC Infectious Diseases, 7, 130. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-7-130

Fonseca, P. A. (2016, February 18). Ramón Silverio: Nunca me traicionaría; así que moriré felizmente. Cubasí.cu. Retrieved from http://www.cubasi.cu/cubasi-noticias-cuba-mundo-ultima-hora/item/48234-ramon-silverio-nunca-me-traicionaria-asi-que-morire-felizmente

Fornet, A. (2008). El quinquenio gris. Revisitando el término. La política cultural en el periodo revolucionario. Memoria y reflexión. Navarro y León (eds.), (p. 174). Havana: Centro Cultural Criterios.

Freeman, B. (2012). What is it About the Art Schools? Places Journal. doi:https://doi.org/10.22

Jacques, P. (2011). Urban Improvisations: The Profanatory Tactics of Spectacularized Spaces. Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, 7(1). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.21083/csieci.v7i1.1390

Lopez-Goicochea, M. (2012, August 3). A hundred years of Virgilio Piñera, l’enfant terrible of Cuban literature. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/aug/03/pinera-cuba-modernism-writer

McFarlane, C. (2017). Fragment urbanism. Life and politics on the margins of the city. Cities in Development, (p. 29). KU Leuven. Retrieved from https://p.cygnus.cc.kuleuven.be/bbcswebdav/pid-21700306-dt-content-rid-122778900_2/courses/B-KUL-S0E06a-1718/McFarlane%2C%20Leuven%20Nov%202017.pdf

Myers, A. G. (2010). Seven Themes in African Urban Dynamics. Nordiska Afrikainsitutet, 1-28.

Navarro, D., León H. (eds.) (2008) La política cultural en el periodo revolucionario. Memoria y reflexión. (p. 174). Havana: Centro Cultural Criterios.

ONEI. (2016). Anuario estadístico de Cuba. Retrieved from http://www.one.cu/aec2016.htm

Perez, J. (2004). Approaches To the Management of HIV/AIDS in Cuba. Perspectives and Practice in Antiretroviral Treatment. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/prev_care/cuba/en/

Redruello, L. (2010). «El lobo, el bosque y el hombre nuevo»: Un final para tres décadas de dogmatismo soviético. Chasqui, 39(1), 120-129. Retrieved from http://limo.libis.be

Reid, M. O. (2017). Esta fiesta se acabó: vida nocturna, orden y desorden social en P.M. y Soy Cuba. Hispanic Research Journal, 18(1), 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/14682737.2016.1238180

Uxo, C. (2006). Renovación y estereotipo en la narrativa breve de los novísimos cubanos. Hispanitas, (2), 109-133. Retrieved from https://research.monash.edu/en/publications/cuban-nov%C3%ADsimos-short-narrative-fiction-renewal-and-stereotype

Zanella, A., Camanho, A. S., & Dias, T. G. (2014). The assessment of cities’ livability integrating human wellbeing and environmental impact. Annals of Operations Research, 226(1), 695–726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-014-1666-7

[1] Chorus from La casa (The House), song inspired by El Mejunje, composed by a member of La Trovuntivitis, a Santa Clara-based music project.

3,039 total views, 1 views today