SOS Andrea Booker Saver of Signs, salvage hunter….

This article comes from the forthcoming issue 2 of Shock City, a DIY print zine with a critical eye on Manchester, in the UK. Find out more on fb, insta & Twitter.

‘We are all archaeologists now’, the Institute of Field Archaeologists recently declared, “because it is a critical inquiry into what it means to be ourselves”, a recognition of the growing ranks of citizen researchers and their determination to open a space for an Archaeology of Us.

This came fast on the heels of All Our Stories, an English Heritage lottery fund examining ‘shoebox’ history; the personal collections of ephemera, family photos and random mementoes – the raw data that’s the chronicle of our ordinary lives – those bits and bobs we typically stash under the bed, memories too personal, too poignant to display but too meaningful and evocative to chuck out.

Growing up, such items were very definitely not history. History was stately homes and municipal museums telling the nation’s grand narrative of conquests, wars and glories through its acquisitions, whether raided from overseas or made by the sweat of our collective brows. History was something we glimpsed through a glass cabinet as consumers, not agents, much less curators or archaeologists in our own right.

A long time ago, before time team or who do you think you are democratized the past, I abandoned my Latin degree for archaeology. This chance to unearth physical connections to the past, direct and tangible, careworn and grubby, and thus encounter its forgotten citizens, was for me the perfect blend of physical and cerebral. Years in soggy fields and boggier ditches got me up close and personal with the complex ways we chose to live, construct social and cultural landscapes, and die – and still do. Create, dismantle, abandon, repeat.

But though it had the potential, the promise, to tell different stories, it remained the preserve of the dreaming spires, the hobby of gentlemen, a pursuit of the privileged and so as a young northern working-class female graduate, I wasn’t even convinced that I was an archaeologist, let alone that all of us could be.

Eventually, I left the muddy fields of prehistory, returning home to discover a contemporary cityscape in tatters. The topography of my family’s roots a post-war archaeology of modernity and hope, its civic and social landmarks, its factories and streetscapes now empty and abandoned, its council estates – homes for everyday heroes, in disrepair and disrepute. Here was a landscape in danger, an urgent rescue project, and a chance to find my very own ancestors.

I co-founded the Manchester modernist society and we declared the city officially a modernist landscape in peril. And English Heritage agreed, acknowledging that ‘recommending modern buildings for listing is one of the most high profile things that (it) does’, though it rarely recommended much outside the capital.

But it was more than a crisis of buildings; buildings are structures, vessels waiting to be brought to life by our work, rest and play. It is people that bring buildings to life -not planners, not politicians – people who make neighbourhoods and turn spaces into places. Cities are giant shoeboxes if you like, filled with the everyday stuff that tells us more than blueprints or street maps ever can. The contemporary past holds tantalizing details of life familiar but fading fast, and even if the buildings could be inventoried, listed, and archived for posterity, in Manchester’s case, the hustle, bustle and cacophony of the streetscape was literally falling off or being thrown into skips like rubbish - their demise seemingly inevitable in this out with the old, in with the new Original, Modern City.

Until at the eleventh hour, as in any great tale, came a Lara Croft for our own times in the shape of Andrea Booker, artist, photographer, skip diver and treasure seeker with a cause. Manchester and the mundane were already her metier, her delight in the ostensibly humdrum a welcome whiff of irreverence to the often grandiose self-importance of art. This eye for treasure in the trash put flesh on the bones of our nascent modernist heritage project.

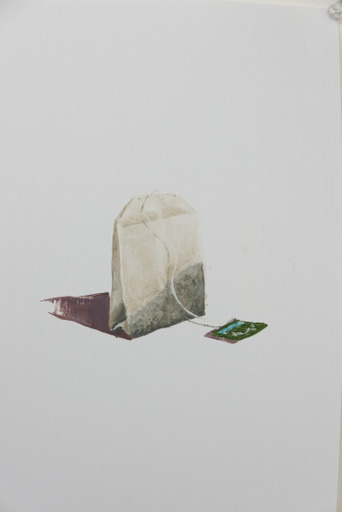

Naturally at home with oils and canvas, her existing body of work was a very contemporary twist on the traditional if unfashionable still life, with affectionate, humorous yet meticulous portrayals of small northern pleasures and the cheeky cheap snack her speciality, her riposte to a city utterly in thrall to the overpriced flat white and hand crafted artisanal tart that will cost you a tenner in N4. This forensic detail, this wry but exhaustive interest in the elevation of the simple, the workaday, the not-iconic, made her interest in dilapidated architectural lettering, building signage and damaged neon, ripe for her particular eye for beauty in the unlikely corners of our streetscapes.

It began when creating the piece SOS (2004), following a one-off salvage from a skip outside the Apollo Theatre. Her second piece FAMOUS (2004) was also formed after another chance salvage; at Stamford House on Chapel St in Salford, near her studio in Islington Mill. Initially, the need to simply save such beautiful signage was the motivation, but soon she began to actively collect them from Manchester and the surrounding areas.

These careworn totems, once so proudly emblazoning our post-war civic amenities and palaces of the people, typographies of our shared social, cultural, and civic landscapes that had revealed multiple narratives of the city past and present and enriched the patina and texture of our built environment – she now radically repurposed. Her canvas was suddenly a giant scrabble board where redundant neon and architectural lettering, could be transformed into almost clairvoyant predictions from our recent past….

It was this text-based practice, this epic, innovative monumentalizing of the discarded and forsaken, spelled out plainly for the myopic, that brought the full glare of the art scene’s attention, accolades, and recognition when it was beautifully explored and revealed during her residency at the Chapman Gallery at the University of Salford.

Like much contemporary art, this new work effectively confronted and straddled so many emerging cultural and contemporary issues that they were recognized both as critical explorations and interrogations of where art, urbanism, gentrification, and heritage were increasingly converging in the new ‘northern powerhouse’. They were also simply the most haunting urban rescue work I’d ever seen, practical, physical, and reinterpreted more thoughtfully and powerfully than many fashionable, high profile interventions into art, archaeology and museum practice, none of which had quite got to the nub of the urgency of the rapid loss of our twentieth-century heritage scape, described by the twentieth-century society as ‘on the cusp of extinction.

When Andrea won the CUBE (Manchester’s late lamented Centre for the Urban and Built Environment) Open, there was a rare opportunity for a longer glimpse into the processes, practices and reflections on the city of this artist cum field archaeologist. Her work eloquently illustrated that action really does speak louder than words, ironically and appropriately enough through the cherishing and displaying of abandoned lettering, their pathetic, patinated and frequently damaged appearance heightening the poignancy of their reprieve. Against the pristine and clinical location of the gallery and separated from their normal surroundings in the street, performing their neon duties of advertising and announcing the commercial, the institutional and spectacular, the subliminal backdrop to our quotidian life, her practice revealed society’s collective schizophrenia and identity crisis – the contradictory demands for newness and innovation, set against the mandatory veneration of vintage, the antique and ‘authentic’, the construction of ‘self’ predicated on what we buy and own, the venues we frequent, our lifestyles and status signposted and directed at every turn.

Her work was urgent, timely yet finite. For Andrea, now, the dig site has gone, her finds, her raw material, carefully packed and stored away. She has moved on and returned to more intimate observations, and back to painting, where the similarity to her signage works reverberate, reflecting her affectionate curiosity in her everyday experience, working with the objects that surround her. Although these objects are commonplace, her paintings elevate them to a place of universal significance.

Her salvage collection remains unique and of its time. What she did with it was a light bulb moment for a nascent archaeo-vernacularist like me, a refugee from prehistory, desperately seeking a methodology for researching our Modernist landscape. She proved definitively that we no longer have to go on a dig to meet our ancestors. Archaeology may have no use for Indy or Lara’s antics, but we DO need more Andreas, more champions of the mundane, champions of all our small triumphs, efforts and heartaches.

We can and must be our own archaeologists now. Our treasures are right in front of our eyes. We just need to see them.

Andrea Booker is a Manchester-based visual artist whose practice is rooted in her wry and affectionate observations of everyday life and its small often overlooked details. She studied Fine Art at Manchester School of Art and has exhibited at group and solo shows, including Home, the Royal Standard, and the Modernist Society. She works across media with text, language and visuals, on canvas, photography, made and found objects, from her studio based at Rogue, www.rastudios.co.uk

5,611 total views, 1 views today